As the founder of LEAD Ministries and an advocate for child rights, I feel compelled to raise urgent alarm about a disturbing global trend: the for

Solving the Palestinian refugee problem: is the ball in Israel's court? By Moshe Ma'oz

Israel has repeatedly asked Arab countries to recognise it and engage in peaceful relations. Most of them rejected these appeals, with the exception of Egypt in 1977 and Jordan in 1994.

However, in 2002 the Arab League announced an unprecedented historical initiative for a comprehensive peace treaty with Israel at the centre of which was the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel.

Successive Israeli governments, headed by Ariel Sharon, Ehud Olmert and Benjamin Netanyahu, either ignored or rejected this initiative even as a starting point for negotiations, thus missing a great opportunity for peace.

The governments of Israel and most of the Jewish-Israeli public were willing to accept the clauses in the Arab proposal that offered an end to the conflict, peace agreements, security arrangements and normal relations with Israel. But they weren't willing to make the necessary concessions in return: withdrawal to the 1967 borders in the West Bank, the Golan Heights and South Lebanon, the establishment of a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital and, most significantly, a solution to the Palestinian refugee problem based on UN resolution 194 from December 1948.

It is true that the clause in the Arab League proposal dealing with the issue of Palestinian refugees was made more rigid as a result of pressure from Syria when it stated that Palestinian refugees would not be accepted as citizens in the Arab states where they have been living since 1948 (or 1967). The implication of this was apparently that the only place where all Palestinian refugees could live was Israel. However, the refugees in question were in Syria and Lebanon, as Jordan already granted full citizenship to its Palestinian residents in 1949.

Moreover, many refugees, especially the estimated 300,000 living in Lebanon, could return to a future Palestinian state in the West Bank. It could also be assumed that in the context of a peace agreement, which would include the return of the Golan Heights, Syria could grant citizenship to the approximately 350,000 Palestinian refugees living within its borders.

The main point of contention regarding the Palestinian refugee issue has to do with the interpretations of UN Resolution 194. Many in Israel understand this resolution to be an affirmation of the "right of return" of all the Palestinian refugees to their homes in Israel: that is, a return of about four million Palestinians, which would destroy Israel's Jewish character.

It is important to understand that this interpretation is erroneous. True, the Palestinian Liberation Organization's (PLO) traditional demand to realise the right of return means a collective return for all Palestinian refugees to their homes in Israel. But UN Resolution 194, which was opposed by the Arab states and the Palestinians at the time, does not even mention the right of return. It states that refugees who wish to return to their homes (on an individual basis) "and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date", and those who do not wish to return should receive compensation. That is, Israel would be given the option to allow or disallow the return of refugees and there is also the alternative of financial compensation.

The Arab League initiative also does not mention the right of return but instead talks about "a just solution to the problem of the Palestinian refugees which will be agreed upon based on UN Resolution 194", which means that Israel must agree to absorb refugees or offer monetary compensation.

My colleagues and I have held long discussions about the subject with Palestinian academics who have adopted a pragmatic approach to solving the problem — the absorption of 100,000 refugees inside Israel in the framework of family reunification, and the payment of collective compensation to the PLO and the Arab nations that host Palestinians and personal compensation to refugees who choose not to return.

But these Palestinian professors have demanded their Israeli interlocutors accept moral responsibility for the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem in the 1948 "Nakba", or the creation of the state of Israel. The Israelis, who agreed to most of the compromise proposals, rejected this demand claiming that Israel did not attack first, but was itself attacked in the war of 1948.

My suggestion is that both sides — the Palestinians and the Israelis — should accept joint responsibility for the creation of the refugee problem, which was caused by a harsh war in which many Palestinians escaped or were expelled by the Israeli army.

It is doubtful whether the Netanyahu government would agree to such a gesture and to the absorption of tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees inside Israel. Just recently, Netanyahu turned to the Palestinians with a public demand to give up the right of return as a precondition for the resumption of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, but it is not possible to order the Palestinians to erase this right from their historical consciousness and hearts.

It would have been more appropriate had he suggested that this right should be realised within a future Palestinian state and that an agreed number of Palestinian refugees could return to Israel in the framework of family reunification, while others would receive compensation for the suffering caused to them. All this would be conditional on a Palestinian commitment to "conclude the refugee chapter" as part of a peace agreement with Israel.

###

* Moshe Ma'oz is professor emeritus of Islamic and Middle Eastern studies at The Hebrew University, and has published many works on the history and politics of Syria and Palestine, and on Arab-Israeli. Article is contributed by CGNews.

However, in 2002 the Arab League announced an unprecedented historical initiative for a comprehensive peace treaty with Israel at the centre of which was the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel.

Successive Israeli governments, headed by Ariel Sharon, Ehud Olmert and Benjamin Netanyahu, either ignored or rejected this initiative even as a starting point for negotiations, thus missing a great opportunity for peace.

The governments of Israel and most of the Jewish-Israeli public were willing to accept the clauses in the Arab proposal that offered an end to the conflict, peace agreements, security arrangements and normal relations with Israel. But they weren't willing to make the necessary concessions in return: withdrawal to the 1967 borders in the West Bank, the Golan Heights and South Lebanon, the establishment of a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital and, most significantly, a solution to the Palestinian refugee problem based on UN resolution 194 from December 1948.

It is true that the clause in the Arab League proposal dealing with the issue of Palestinian refugees was made more rigid as a result of pressure from Syria when it stated that Palestinian refugees would not be accepted as citizens in the Arab states where they have been living since 1948 (or 1967). The implication of this was apparently that the only place where all Palestinian refugees could live was Israel. However, the refugees in question were in Syria and Lebanon, as Jordan already granted full citizenship to its Palestinian residents in 1949.

Moreover, many refugees, especially the estimated 300,000 living in Lebanon, could return to a future Palestinian state in the West Bank. It could also be assumed that in the context of a peace agreement, which would include the return of the Golan Heights, Syria could grant citizenship to the approximately 350,000 Palestinian refugees living within its borders.

The main point of contention regarding the Palestinian refugee issue has to do with the interpretations of UN Resolution 194. Many in Israel understand this resolution to be an affirmation of the "right of return" of all the Palestinian refugees to their homes in Israel: that is, a return of about four million Palestinians, which would destroy Israel's Jewish character.

It is important to understand that this interpretation is erroneous. True, the Palestinian Liberation Organization's (PLO) traditional demand to realise the right of return means a collective return for all Palestinian refugees to their homes in Israel. But UN Resolution 194, which was opposed by the Arab states and the Palestinians at the time, does not even mention the right of return. It states that refugees who wish to return to their homes (on an individual basis) "and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date", and those who do not wish to return should receive compensation. That is, Israel would be given the option to allow or disallow the return of refugees and there is also the alternative of financial compensation.

The Arab League initiative also does not mention the right of return but instead talks about "a just solution to the problem of the Palestinian refugees which will be agreed upon based on UN Resolution 194", which means that Israel must agree to absorb refugees or offer monetary compensation.

My colleagues and I have held long discussions about the subject with Palestinian academics who have adopted a pragmatic approach to solving the problem — the absorption of 100,000 refugees inside Israel in the framework of family reunification, and the payment of collective compensation to the PLO and the Arab nations that host Palestinians and personal compensation to refugees who choose not to return.

But these Palestinian professors have demanded their Israeli interlocutors accept moral responsibility for the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem in the 1948 "Nakba", or the creation of the state of Israel. The Israelis, who agreed to most of the compromise proposals, rejected this demand claiming that Israel did not attack first, but was itself attacked in the war of 1948.

My suggestion is that both sides — the Palestinians and the Israelis — should accept joint responsibility for the creation of the refugee problem, which was caused by a harsh war in which many Palestinians escaped or were expelled by the Israeli army.

It is doubtful whether the Netanyahu government would agree to such a gesture and to the absorption of tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees inside Israel. Just recently, Netanyahu turned to the Palestinians with a public demand to give up the right of return as a precondition for the resumption of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, but it is not possible to order the Palestinians to erase this right from their historical consciousness and hearts.

It would have been more appropriate had he suggested that this right should be realised within a future Palestinian state and that an agreed number of Palestinian refugees could return to Israel in the framework of family reunification, while others would receive compensation for the suffering caused to them. All this would be conditional on a Palestinian commitment to "conclude the refugee chapter" as part of a peace agreement with Israel.

###

* Moshe Ma'oz is professor emeritus of Islamic and Middle Eastern studies at The Hebrew University, and has published many works on the history and politics of Syria and Palestine, and on Arab-Israeli. Article is contributed by CGNews.

You May Also Like

Even before 2026 began, we were never on track to deliver on gender equality and human right to health and broader development justice. For e

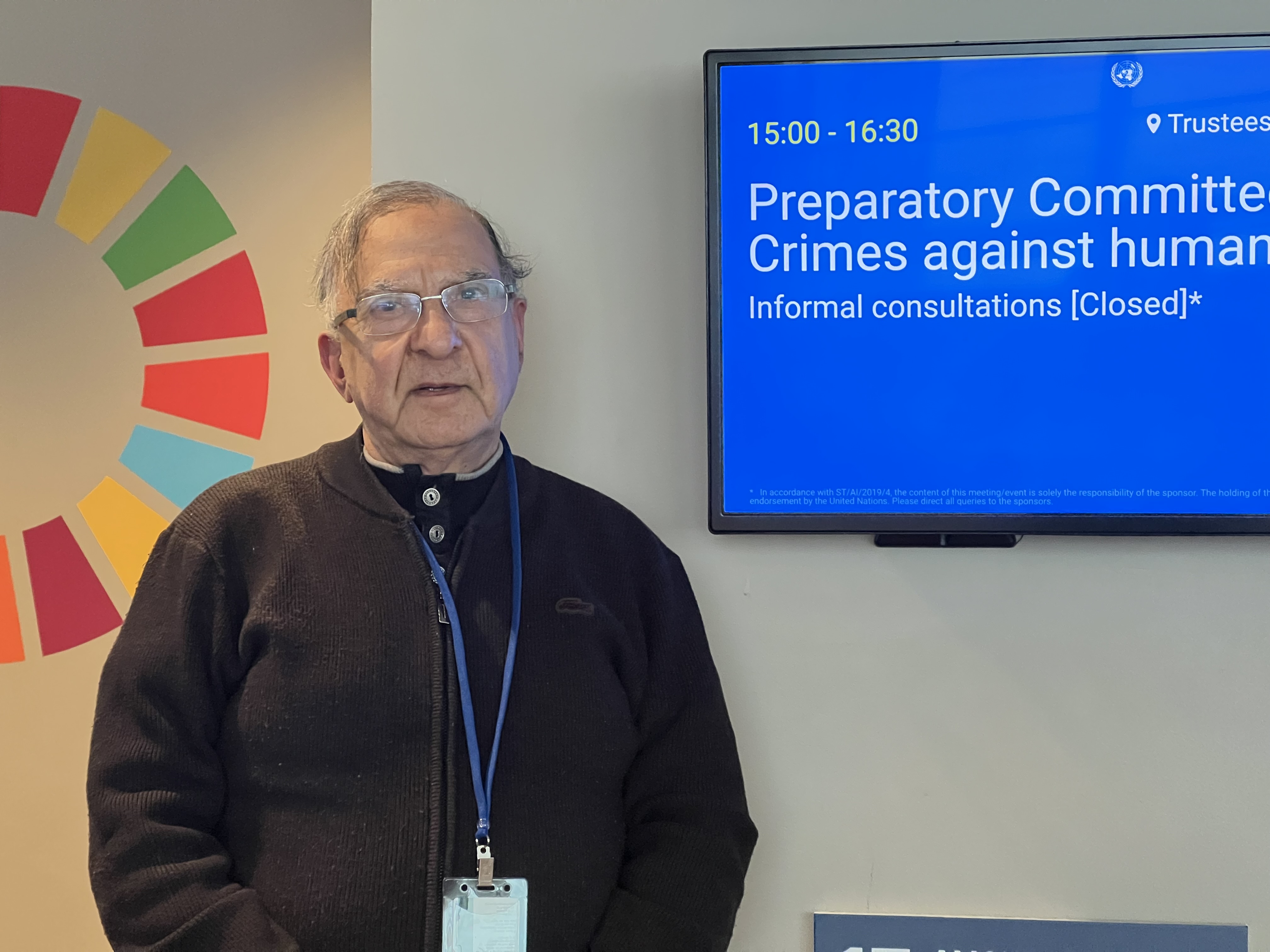

New York: Crimes against humanity represent one of the most serious affronts to human dignity and collective conscience. They embody patterns of wi

"Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" By Nazir S Bhatti

On demand of our readers, I have decided to release E-Book version of "Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" on website of PCP which can also be viewed on website of Pakistan Christian Congress www.pakistanchristiancongress.org . You can read chapter wise by clicking tab on left handside of PDF format of E-Book.