As the founder of LEAD Ministries and an advocate for child rights, I feel compelled to raise urgent alarm about a disturbing global trend: the for

Borders without religions or religions without borders? By Dana Nawzar Ali

Can religion comprise a country's all-encompassing identity? How does connecting religion to a particular place affect our perception of that place?

Outsiders' views about a religion can be shaped by the way it is linked to a certain nation or geographical area, and in a world where religion is at the centre of many political discussions, we must understand the problems that can arise when we use religious terms to describe a place.

When we watch the news or read an article, we often see terms like "Islamic world" or "Muslim countries" used indiscriminately. As an Iraqi, I live in the "Islamic world" and find this terminology odd. After all, we would find it awkward if someone described the European Union as the "Christian" union. We would think that the speaker was either living in the Middle Ages or was a religious fanatic. Using Islam and its derivations to describe and identify geographical places, however, seems to be entirely acceptable.

In this age of quick newsbytes, these phrases have affected Islam's image. As a result, any appalling action by individuals from Muslim-majority countries is interpreted as condoned by Islam. For example, in his book, Secrets of the Koran, Canadian Christian missionary Don Richardson accuses Islam of being totalitarian because of Iraq's late president, Saddam Hussein when, in fact, Saddam Hussein's totalitarianism was not derived from Islam, but from his secular political ideology.

How can a country, comprised of individuals with different beliefs and values, have a fixed religious identity? How can we call my country, Iraq, a "Muslim country" when it has a non-Muslim population, however small, and when the religious identity of its people may change in the future?

Calling Iraq a "Muslim country" isolates its Christian population. Sunnis and Shi'a are divided because they adhere to political beliefs that are now aligned with their religious confessions. In Iraq, political groups vote in elections as representatives of their sects and ethnicities. So it's very rare to see a Sunni voting for a Shi'a candidate – and vice versa.

Within a particular country, people's perception of religion is easily mixed with political and ethnic identities – which unfortunately can lead to a polarisation of society, as we've seen in Iraq. It is this type of thinking – which draws religion into politics – that turns neighbours into enemies.

Rather than attempting to pin down a country's particular religious identity, we should emphasise its national identity, which is what unifies Iraq's citizens.

Mistakenly using religious instead of national labels can also affect how a religion is perceived with regard to human rights and liberties. If a country in the Middle East has a poor human rights record, for example, people might ascribe this leniency as permissible in Islam because the country is considered part of the "Islamic world".

The consequences of trying to limit religion to geographical borders are detrimental to both the religion and the people involved. The first step to reverse this downward spiral is to separate geography and national identity from religion – which will help prevent the isolation of groups that do not adhere to the majority's religious identity. The second step is to make a distinction between religious, ethnic and political identity to avoid the confusion of religious values with ethnic customs and political interests.

###

* Dana Nawzar Ali is currently a sophomore studying international relations and political science at the American University of Iraq in Sulaimani. This article was written for the Common Ground News Service (CGNews).

Outsiders' views about a religion can be shaped by the way it is linked to a certain nation or geographical area, and in a world where religion is at the centre of many political discussions, we must understand the problems that can arise when we use religious terms to describe a place.

When we watch the news or read an article, we often see terms like "Islamic world" or "Muslim countries" used indiscriminately. As an Iraqi, I live in the "Islamic world" and find this terminology odd. After all, we would find it awkward if someone described the European Union as the "Christian" union. We would think that the speaker was either living in the Middle Ages or was a religious fanatic. Using Islam and its derivations to describe and identify geographical places, however, seems to be entirely acceptable.

In this age of quick newsbytes, these phrases have affected Islam's image. As a result, any appalling action by individuals from Muslim-majority countries is interpreted as condoned by Islam. For example, in his book, Secrets of the Koran, Canadian Christian missionary Don Richardson accuses Islam of being totalitarian because of Iraq's late president, Saddam Hussein when, in fact, Saddam Hussein's totalitarianism was not derived from Islam, but from his secular political ideology.

How can a country, comprised of individuals with different beliefs and values, have a fixed religious identity? How can we call my country, Iraq, a "Muslim country" when it has a non-Muslim population, however small, and when the religious identity of its people may change in the future?

Calling Iraq a "Muslim country" isolates its Christian population. Sunnis and Shi'a are divided because they adhere to political beliefs that are now aligned with their religious confessions. In Iraq, political groups vote in elections as representatives of their sects and ethnicities. So it's very rare to see a Sunni voting for a Shi'a candidate – and vice versa.

Within a particular country, people's perception of religion is easily mixed with political and ethnic identities – which unfortunately can lead to a polarisation of society, as we've seen in Iraq. It is this type of thinking – which draws religion into politics – that turns neighbours into enemies.

Rather than attempting to pin down a country's particular religious identity, we should emphasise its national identity, which is what unifies Iraq's citizens.

Mistakenly using religious instead of national labels can also affect how a religion is perceived with regard to human rights and liberties. If a country in the Middle East has a poor human rights record, for example, people might ascribe this leniency as permissible in Islam because the country is considered part of the "Islamic world".

The consequences of trying to limit religion to geographical borders are detrimental to both the religion and the people involved. The first step to reverse this downward spiral is to separate geography and national identity from religion – which will help prevent the isolation of groups that do not adhere to the majority's religious identity. The second step is to make a distinction between religious, ethnic and political identity to avoid the confusion of religious values with ethnic customs and political interests.

###

* Dana Nawzar Ali is currently a sophomore studying international relations and political science at the American University of Iraq in Sulaimani. This article was written for the Common Ground News Service (CGNews).

You May Also Like

Even before 2026 began, we were never on track to deliver on gender equality and human right to health and broader development justice. For e

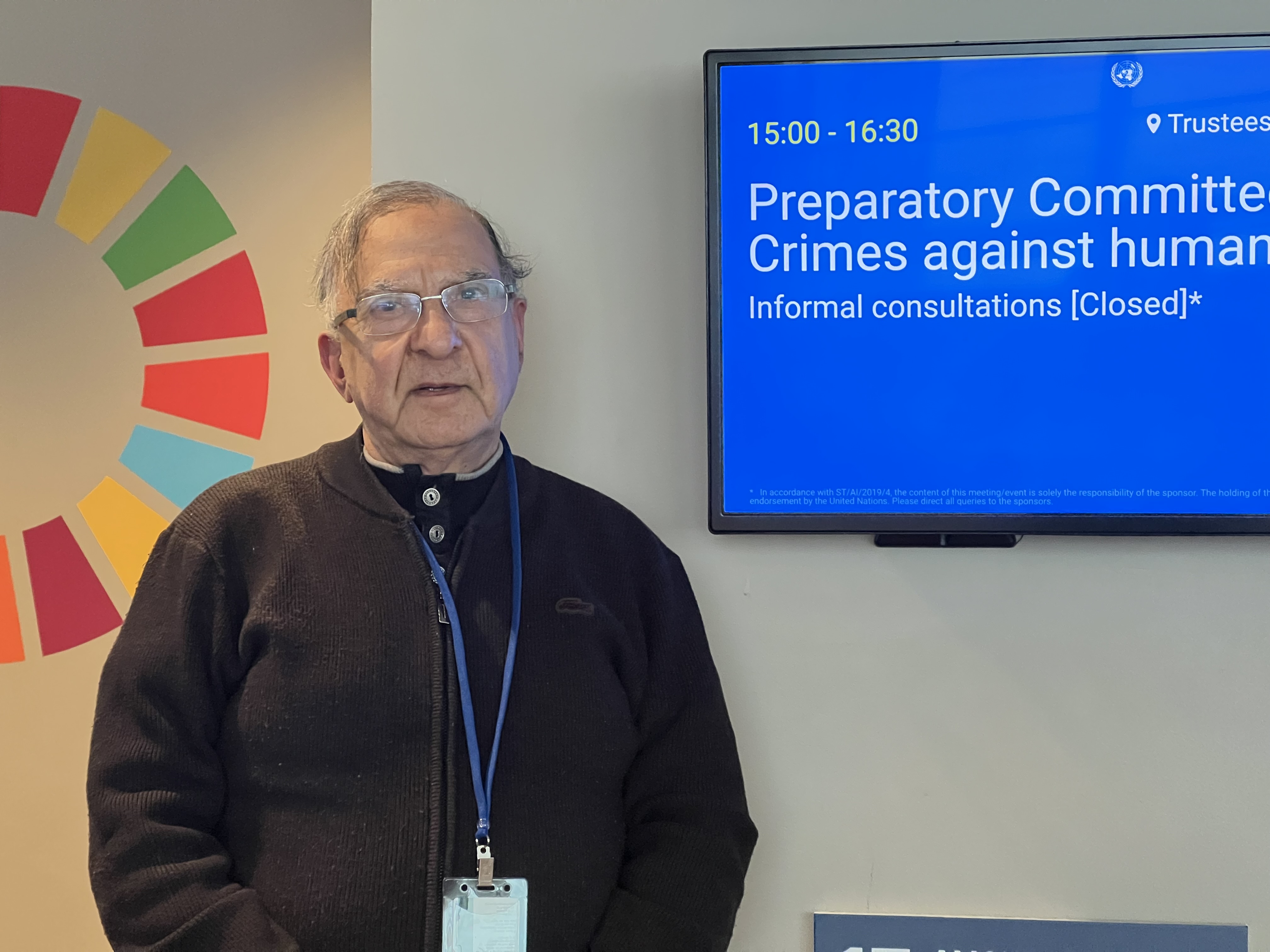

New York: Crimes against humanity represent one of the most serious affronts to human dignity and collective conscience. They embody patterns of wi

"Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" By Nazir S Bhatti

On demand of our readers, I have decided to release E-Book version of "Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" on website of PCP which can also be viewed on website of Pakistan Christian Congress www.pakistanchristiancongress.org . You can read chapter wise by clicking tab on left handside of PDF format of E-Book.