As the founder of LEAD Ministries and an advocate for child rights, I feel compelled to raise urgent alarm about a disturbing global trend: the for

In Kabul, it's deadly at the top: By Cheryl Benard

In 2003, I met Afghan President Hamid Karzai under somewhat unusual circumstances. The Rand Corporation, my employer, and Sesame Workshop had teamed up to create an Afghan version of Sesame Street. We were designing short video episodes to be shown to the new generation of post-Taliban Afghan schoolchildren.

Karzai had agreed to appear in one of the episodes. The plan was to film a group of Afghan-American children, decked out in Afghan folklore clothing, with Karzai during one of his visits to Washington, DC. The undertaking, which had been difficult enough to arrange, seemed jinxed.

There was a blizzard the day of the filming, and volunteers with four-wheel drive vehicles had to be dispatched to take the children to Blair House, the official guesthouse for heads of state. Karzai was hours late, held up by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and when he finally arrived, he was furious. He had been insulted, he felt, by Congress, grilled about Afghanistan's growing drug trade and corruption.

He had just fired his ambassador, whom he blamed for the debacle, and as he stomped through Blair House in a rage, I thought it was curtains for my little project. Then he saw the children, and his mood brightened. He summoned them over, and as they settled down to chat, the relieved film crew began to roll the tape. Karzai told the children about his favourite bedtime stories as a child, what he remembered of his elementary school days, what games he had most enjoyed and how many countries he had visited.

The children were adorable, and Karzai seemed to be relaxing – until a young girl asked him what he liked best about being president. A lengthy silence fell. He seemed to forget where he was. His face grew dark, and the adults in the room began to exchange worried glances. At last he spoke.

"Nothing", he said.

As I think about the upcoming elections in Afghanistan, scheduled for August 2009, I often remember that moment.

In retrospect, 2003 was a happy, positive time for Karzai. The world, and his own citizens, still loved him. Even the tough questions from US lawmakers had been intended to understand the scope of the problem and find a way to help Afghanistan, not to embarrass him.

Today, Karzai stands accused of tolerating the involvement of his brothers in massive corruption and in the drug trade, of vacillation and of incompetence.

Many countries have stormy histories. But Afghanistan is exceptional in its track record of first venerating, then ferociously turning on, its leaders. On that snowy day in Washington, Karzai was still the world's darling; at home, he held the status of a potentate.

Not counting Karzai, 29 individuals have ruled Afghanistan since 1700. Of these, only four served out their terms and died a natural death. The others were dethroned, assassinated, imprisoned, deposed and killed, deposed and exiled, deposed and hanged, beaten to death and so forth.

Portraits and photographs show these kings and presidents in their glory days – handsome, proud, with intelligent eyes and uplifted chins. Some were traditional. Others spent time abroad and came back with what they thought were compelling new ideas for reform and progress. Regardless, they were first feted, then hated and finally destroyed.

Today, the Afghan people need a lot of things – security, electricity, hospitals and alternatives to growing poppies. Looking at their history, I submit that what they also need is something we refer to as "respect for the office".

###

* Cheryl Benard co-directs the Alternative Strategies Initiative at the Rand Corporation and has worked extensively in Afghanistan. This article is distributed by the Common Ground News Service (CGNews) with permission from the author.

**********

Karzai had agreed to appear in one of the episodes. The plan was to film a group of Afghan-American children, decked out in Afghan folklore clothing, with Karzai during one of his visits to Washington, DC. The undertaking, which had been difficult enough to arrange, seemed jinxed.

There was a blizzard the day of the filming, and volunteers with four-wheel drive vehicles had to be dispatched to take the children to Blair House, the official guesthouse for heads of state. Karzai was hours late, held up by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and when he finally arrived, he was furious. He had been insulted, he felt, by Congress, grilled about Afghanistan's growing drug trade and corruption.

He had just fired his ambassador, whom he blamed for the debacle, and as he stomped through Blair House in a rage, I thought it was curtains for my little project. Then he saw the children, and his mood brightened. He summoned them over, and as they settled down to chat, the relieved film crew began to roll the tape. Karzai told the children about his favourite bedtime stories as a child, what he remembered of his elementary school days, what games he had most enjoyed and how many countries he had visited.

The children were adorable, and Karzai seemed to be relaxing – until a young girl asked him what he liked best about being president. A lengthy silence fell. He seemed to forget where he was. His face grew dark, and the adults in the room began to exchange worried glances. At last he spoke.

"Nothing", he said.

As I think about the upcoming elections in Afghanistan, scheduled for August 2009, I often remember that moment.

In retrospect, 2003 was a happy, positive time for Karzai. The world, and his own citizens, still loved him. Even the tough questions from US lawmakers had been intended to understand the scope of the problem and find a way to help Afghanistan, not to embarrass him.

Today, Karzai stands accused of tolerating the involvement of his brothers in massive corruption and in the drug trade, of vacillation and of incompetence.

Many countries have stormy histories. But Afghanistan is exceptional in its track record of first venerating, then ferociously turning on, its leaders. On that snowy day in Washington, Karzai was still the world's darling; at home, he held the status of a potentate.

Not counting Karzai, 29 individuals have ruled Afghanistan since 1700. Of these, only four served out their terms and died a natural death. The others were dethroned, assassinated, imprisoned, deposed and killed, deposed and exiled, deposed and hanged, beaten to death and so forth.

Portraits and photographs show these kings and presidents in their glory days – handsome, proud, with intelligent eyes and uplifted chins. Some were traditional. Others spent time abroad and came back with what they thought were compelling new ideas for reform and progress. Regardless, they were first feted, then hated and finally destroyed.

Today, the Afghan people need a lot of things – security, electricity, hospitals and alternatives to growing poppies. Looking at their history, I submit that what they also need is something we refer to as "respect for the office".

###

* Cheryl Benard co-directs the Alternative Strategies Initiative at the Rand Corporation and has worked extensively in Afghanistan. This article is distributed by the Common Ground News Service (CGNews) with permission from the author.

**********

You May Also Like

Even before 2026 began, we were never on track to deliver on gender equality and human right to health and broader development justice. For e

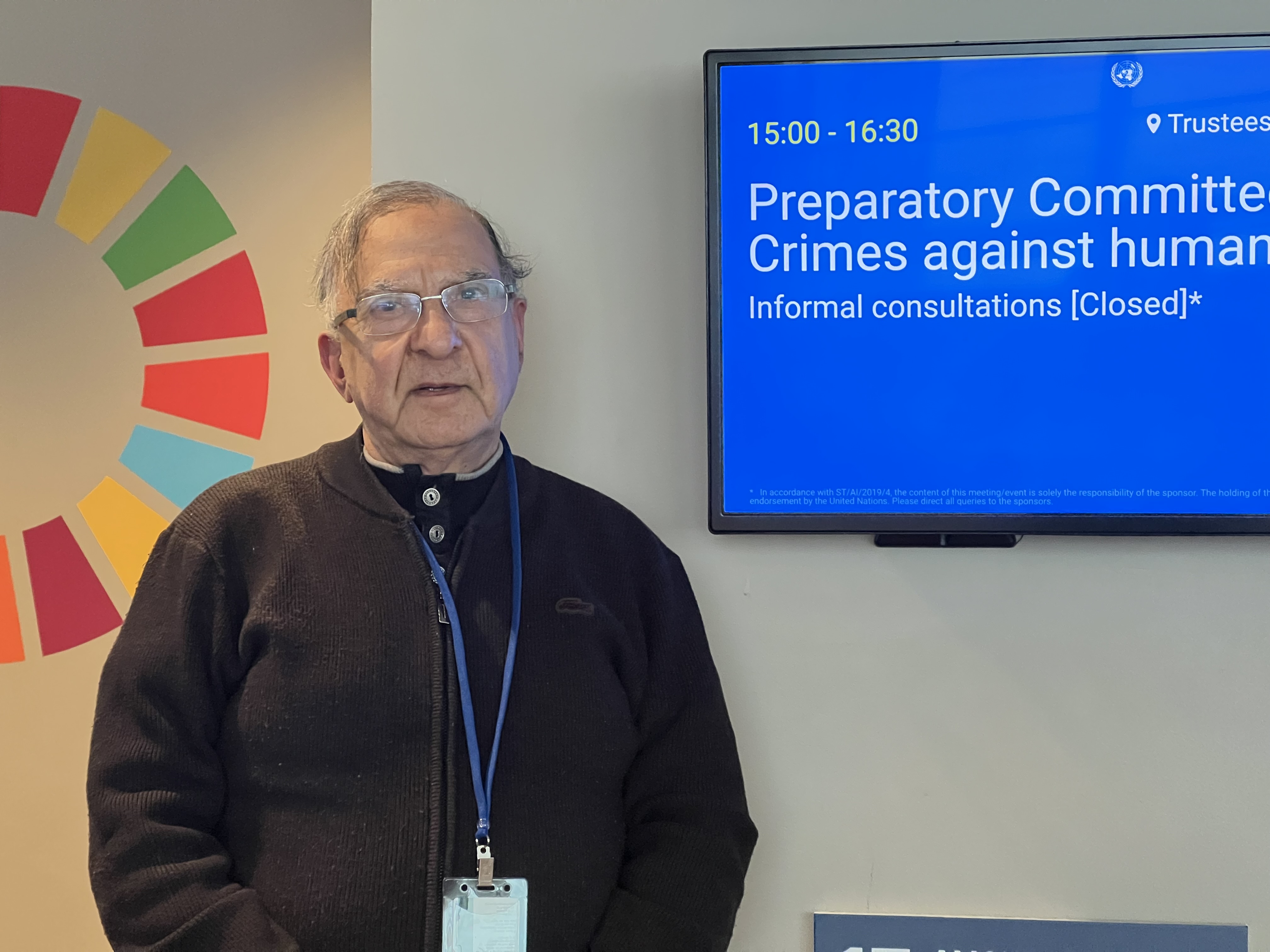

New York: Crimes against humanity represent one of the most serious affronts to human dignity and collective conscience. They embody patterns of wi

"Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" By Nazir S Bhatti

On demand of our readers, I have decided to release E-Book version of "Trial of Pakistani Christian Nation" on website of PCP which can also be viewed on website of Pakistan Christian Congress www.pakistanchristiancongress.org . You can read chapter wise by clicking tab on left handside of PDF format of E-Book.